By Mariah C. Shéba Baptiste

Let us clarify this once for all : the Haitian Revolution was never just a slave revolt. That phrase is a colonial sedative, a way to turn the unthinkable into folklore. It sounds objective, but it carries centuries of condescension. It turns thought into accident, philosophy into riot, and dignity into episode.

In Saint-Domingue, now Haiti, no one called themselves a slave. They said nèg—a word that, in Haitian Creole, means human, moun, existence itself before color or condition. To call the 1803–1804 struggle a “slave uprising” is to erase its reason, to pretend those who dismantled an empire acted by chaos rather than conscience. It is the echo of an older violence: the West’s inability to imagine the Black as a being who can think.

“… the peculiar characteristic of being unthinkable even as it happened.”

M-R. Trouillot

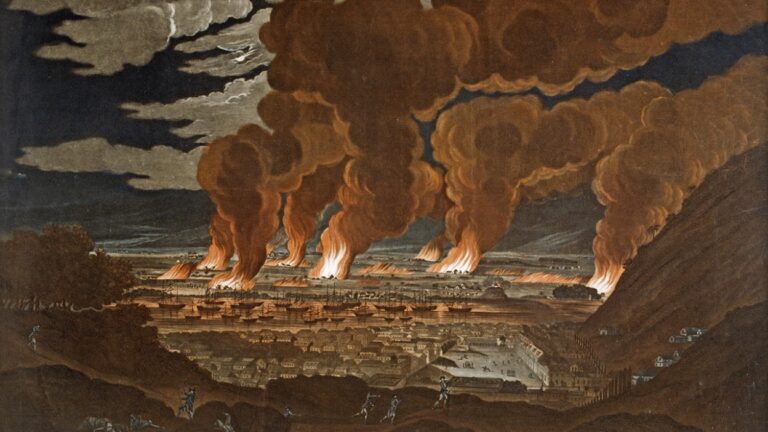

Vertières—November 18, 1803—was not a spontaneous explosion but an organized grammar of defiance. The Battle of Vertières ended an empire built on sugar, skin, and silence. The Western imagination still calls it a revolt because it cannot admit that the enslaved could produce an idea.

A revolt looks backward; a revolution invents forward. The former screams; the latter decides. What happened in Saint-Domingue was decision—perhaps the most lucid political experiment of the modern world.

Michel-Rolph Trouillot wrote that the Haitian Revolution entered history “with the peculiar characteristic of being unthinkable even as it happened.” It was not obscure; it was too clear. It exposed the hypocrisy of men who declared liberty while trading flesh, who wrote that all humans are born free, then sold them like mangoes on a Saturday morning market. The Enlightenment looked into the mirror and flinched.

“If one denies the equality of races, one denies humanity itself.”

A. Firmin

The etymology itself betrays the bias. Revolt comes from revoltere—to turn back, to reject. A revolt is reactionary, brief, emotional. A revolution invents a new world.

Saint-Domingue’s revolution was not a spasm of rage but the deliberate creation of a republic where no human could be owned.

Europe consoles itself with euphemisms. Rome had “servants.” The Vikings had “captives.” But the Atlantic world invented something new: slavery by skin, sanctified by God, rationalized by pseudo-science. When whiteness became theology, blackness became heresy.

Before anthropology was decolonized, Saint-Domingue’s insurgents had already done the work. Later, Anténor Firmin would summarize it scientifically in De l’égalité des races humaines (1885): “If one denies the equality of races, one denies humanity itself.”

A century after Haiti’s revolution, geneticist Richard Lewontin confirmed the same truth: “Eighty-five percent of human variation occurs within populations, not between them.” Races were never biology; they were economics with divine marketing.

Europe turned bondage into beauty. Its painters and sculptors transformed suffering into aesthetic redemption. Carpeaux carved Pourquoi naître esclave ? and called it empathy. Canova perfected a slave without a face.

Even abolitionist art turned pain into spectacle—moral pornography disguised as compassion. Anne Lafont later called it “the naturalization of hierarchy under the veil of aesthetic humanism.”

Cinema inherited the same grammar: Gone with the Wind glorified obedience; Amistad centered the white lawyer; 12 Years a Slave turned agony into poetry. The camera knows how to film Black pain; it stammers at the sight of Black freedom.

“We do not paint to resemble, we paint to resurrect.”

Tiga

Haiti broke that frame. The Revolution destroyed not only plantations but the gaze that required them.

From Hyppolite’s Les Sirènes (1946) to Roumain’s peasants, from the drums of Saint-Soleil to the cries of Vieux-Chauvet, Haitian art did not simply decolonize beauty—it dethroned it.

Hector Hyppolite’s gods do not suffer; they reign. Wilson Bigaud’s Le Baptême du Vodou replaces Christian ritual with the ceremony of sovereignty. Philomé Obin paints Dessalines not as saint, but as insurgent haloed by the fire of Vertières.

Then came the Saint-Soleil movement in the 1970s—Tiga, Lévoy Exil, Prospère Pierre-Louis—peasants who painted freedom without reading Hegel. “We do not paint to resemble,” Tiga said. “We paint to resurrect.”

In literature, the same uprising burned. Price-Mars demanded that Haiti stop apologizing for its gods. Jacques Roumain made the peasant the measure of the world. Marie Vieux-Chauvet turned trauma into feminine rebellion. Jacques-Stéphen Alexis wrote the worker as prophet.

Where Europe painted guilt, Haiti painted metaphysics. In Edouard Duval-Carrié’s The Kingdom of This World (1996), silhouettes of slaves float like constellations across indigo skies. Jean-Ulrick Désert veils Venus with sequins, mocking the gaze that once stripped and studied us. Kara Walker’s silhouettes decapitate the romance of whiteness; Kehinde Wiley replaces Napoleon with a boy from Brooklyn.

Europe painted confession; Haiti painted resurrection.

Even today, the same color mythology poisons the world: white as purity, black as shadow. Heaven above, darkness below.

When we say Vodou, they shudder; when they say Christianity, they kneel. Yet Vodou is philosophy, memory, ecology—the survival of African metaphysics under European contempt.

Its lwa are metaphors of sovereignty, its drums the rhythm of remembrance. To fear Vodou is to fear what cannot be colonized.

“We were never slaves; we were people deprived of liberty.”

J. Price-Mars

Then came Dessalines—the most misunderstood of founders. After Toussaint Louverture’s betrayal, he unified the factions, turned rebellion into government, and in 1804 dared to say what Europe whispered: freedom could be Black.

His 1805 Constitution abolished slavery forever, declared all citizens equal, renamed every Haitian “Black,” and outlawed foreign ownership of land. He offered asylum to the persecuted: “Any African, American, Indian, Asian, even European or descendant of these races shall be recognized as Haitian and as free the moment they touch our soil.”

It was socialism before Marx, asylum before the Geneva Convention, humanism before UNESCO.

Europe called it barbarism. In truth, it was the first universal declaration of human rights written in blood and dust.

Dessalines imagined Haiti as refuge. Long before human rights became slogans, Haiti practiced them. Exiles from every shore found protection there.

Jean Price-Mars reminded us: “We were never slaves; we were people deprived of liberty.” Colonialism tried to unname the Black; the Revolution renamed him human.

Laënnec Hurbon later wrote, “Haiti was born in violence”—not cruelty, but resistance: the violence of having to prove one’s right to breathe.

“Europe preferred the idea of freedom to its realization…”

S. Buck-Morss

France, of course, raised the Declaration of the Rights of Man with one hand and signed slave ledgers with the other. When the enslaved read those words and whispered, if all men, then us too, the world convulsed.

Europe preferred the idea of liberty to its realization. Haiti made it real—and therefore unbearable.

It was not the imitation of the French Revolution; it was its correction. “Europe preferred the idea of freedom to its realization,” wrote Susan Buck-Morss. “Haiti gave philosophy its proof.”

The shock traveled: Bolívar found arms and refuge in Haiti; the Louisiana Purchase reshaped America because France lost Saint-Domingue. A century later, the UN merely bureaucratized what Dessalines had already proclaimed in Kreyòl.

UNESCO now calls Haiti “the first universal act of human rights.” Imagine the Emperor’s ironic smile.

Birth, Not Chaos

What frightens the world still is the completeness of that act. Haiti did not merely abolish slavery; it abolished the right to enslave. It did not beg for inclusion in humanity; it redefined it.

The world still prefers Toussaint the diplomat to Dessalines the radical. It loves metaphors, not mirrors.

The Haitian Revolution remains the most dangerous event of modern history because it was perfect. It proved that freedom is not granted by charters but claimed by those who refuse to kneel.

The Enlightenment invented the idea of the human; Haiti gave it a face.

So no—there were never slaves in Saint-Domingue. There were humans who refused the name. When they rose, they did not just revolt; they founded.

The world calls it chaos. We call it birth.

Grenadye alaso.

References

- Benoist, M.-G. (1800). Portrait of a Black Woman. Musée du Louvre, Paris.

- Bigaud, W. (1950). Le Baptême du Vodou. Port-au-Prince.

- Buck-Morss, S. (2000). Hegel and Haiti. Critical Inquiry, 26(4), 821–865.

- Carpeaux, J.-B. (1868). Pourquoi naître esclave? Musée d’Orsay, Paris.

- Childs, A. (2019). Angélique’s Cry: The Representation of Slavery in French Art. Yale University Press.

- Constitution impériale d’Haïti. (1805).

- Dayan, J. (1995). Haiti, History, and the Gods. University of California Press.

- Dubois, L. (2004). Avengers of the New World: The Story of the Haitian Revolution. Harvard University Press.

- Duffaut, P. (1950s). Ville imaginaire. Musée d’Art Haïtien, Port-au-Prince.

- Duval-Carrié, E. (1996). The Kingdom of This World. Pérez Art Museum, Miami.

- Fanon, F. (1952). Peau noire, masques blancs. Seuil.

- Fick, C. (1990). The Making of Haiti: The Saint-Domingue Revolution from Below. University of Tennessee Press.

- Firmin, A. (1885). De l’égalité des races humaines. Cotillon.

- Gauvin, L. (2003). Les figures de l’esclave dans la peinture française du XIXe siècle. Revue de l’art, 142(1), 25–41.

- Geggus, D. (2001). The Impact of the Haitian Revolution in the Atlantic World. University of South Carolina Press.

- Hartman, S. (1997). Scenes of Subjection: Terror, Slavery, and Self-Making in Nineteenth-Century America. Oxford University Press.

- Hyppolite, H. (1946–1950). Les Sirènes; Ogoun Feray. Musée d’Art Haïtien, Port-au-Prince.

- James, C. L. R. (1938). The Black Jacobins: Toussaint L’Ouverture and the San Domingo Revolution. Secker & Warburg.

- Lafont, A. (2019). L’art et la race: L’Africain (tout) contre l’œil des Lumières. Les Presses du Réel.

- Lewontin, R. C. (1972). The apportionment of human diversity. Evolutionary Biology, 6, 381–398.

- Mbembe, A. (2013). Critique de la raison nègre. La Découverte.

- Mercer, K. (1994). Welcome to the Jungle: New Positions in Black Cultural Studies. Routledge.

- Miller, C. (2008). The French Atlantic Triangle: Literature and Culture of the Slave Trade. Duke University Press.

- Nama, A. (2015). Race on the QT: Blackness and the Films of Quentin Tarantino. University of Texas Press.

- Pontecorvo, G. (Director). (1969). Burn! United Artists.

- Price-Mars, J. (1928). Ainsi parla l’oncle. Imprimerie de l’État.

- Quijano, A. (2000). Coloniality of power, Eurocentrism, and Latin America. Nepantla: Views from South, 1(3), 533–580.

- Robinson, C. J. (1983). Black Marxism: The Making of the Black Radical Tradition. University of North Carolina Press.

- Roumain, J. (1944). Gouverneurs de la rosée. Éditions Fardin.

- Trouillot, M.-R. (1995). Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History. Beacon Press.

- Vieux-Chauvet, M. (1968). Amour, colère et folie. Gallimard.

- Walker, K. (1994). Gone, an Historical Romance of a Civil War as It Occurred Between the Dusky Thighs of One Young Negress and Her Heart. Museum of Modern Art.

- Wiley, K. (2005). Napoleon Leading the Army over the Alps. Brooklyn Museum.