If I say that I listen to music with my skin rather than my ears, a certain microcosm will know exactly what I mean. What follows, written from a fully assumed subjectivity, is meant first for those who will hear me through their nerves, and perhaps later for the others, those who prefer to wait for a “mainstream” opinion before taking a stand. Still, I’m convinced of one thing: the more subjective you are, the closer you get to the truth, and the better you resonate with the universal. But that’s another debate.

In my relationship with music, I’ve noticed that men’s voices calm and instruct me, while women’s voices heal me. To be clear, I’m not talking about biology or gender, but natural sensitivity. When I listen to Nina Simone, for instance, I don’t process her through the brain—I receive her. From the very first line of I Put a Spell on You, Nina tells me everything. I know everything, I feel everything. The record could stop right there and the experience would still be complete.

I also have an almost pathological appetite for what we call Black Music: from Negro spirituals to blues, from jazz to soul, from funk to reggae, from R&B to hip-hop, all the way to folk and even a bit of country by Black artists. As for zouk, compas, and meringue, they’re part of my Caribbean DNA, so I place them in a category of love by default. And though I had my share of music-theory lessons and cello practice back in the day, I’m not speaking here as a technician but as a music lover moved by vibration.

I say all this to set the scene: this text is written with the spinal cord. It’s about voices—those of women who, through time, have carried Haiti in their breath, sung it, transmitted it, embodied it. I call them divas, not out of caprice, but because they concentrate something rare: mastery of an art, an identity owned, and an aura bordering on the mystical.

And to broaden the picture so you fully get my point, I’d say some female voices alone embody the emotional geography of a nation. It’s hard not to fall in love with the France of Édith Piaf, not to desire the Mexico of Selena Quintanilla-Pérez, not to be electrified by the Cuba of Celia Cruz, not to smile with the Martinique of Jocelyne Béroard, or not to admire the Canada of Céline Dion. And what about the United States of Michael Jackson (not a joke), today nearly conquered by Taylor Swift since white America has grown weary of Beyoncé Knowles. In short, some voices define nations; others transcend them. And in that cartography, Haiti too has its singing stars.

What Makes a Haitian Diva?

The word diva, once reserved for opera prima donnas or temperamental stars, has changed shades. Today it evokes the icon, the strength, the woman who stands tall without permission. In my lexicon, a Haitian diva is neither a job title nor a trophy, but a collective recognition earned through a rare combination of elements:

- excellence and mastery of her art;

- authentic representation of Haitian culture;

- a touch of universality;

- a career that withstands time;

- a qualitative influence on her generation.

Easy to list, nearly impossible to check them all.

Sorting the Field

And that’s where the sorting begins. Because if every “Grande Dame” isn’t necessarily a “Diva,” we still have to make the distinction and take the risk. So yes, for those already grinding their teeth, please relax. I’ll explain.

I sifted through a long list of remarkable women singers: Minette, Andrée Lescot, Andrée Gauthier Canez, Émerante de Pradines, Toto Bissainthe, Yole Dérose, TiCorn, Farah Juste, Gina Dupervil, Yanick Étienne, Manzè, Lunise Morse, Mélissa Laveaux, Blondedy Ferdinand, Marie Bedjine, Anie Alerte, and even James Germain (no, still not a joke). They’re all admirable, but few check every box. Some lack universality, others aura or longevity. Some shone brightly without ever transcending. Because being a diva isn’t just about talent; it’s an almost cosmic alignment between voice, presence, and destiny.

The earliest name to emerge is Minette, alongside her sister Lise in eighteenth-century Saint-Domingue. Élisabeth Alexandrine Louise Ferrand, known as Minette, and her sibling were the first Creole women, born to a freed mother and a white father, to perform publicly. In a world built on segregation, standing on stage was already an act of rebellion. Their talent transcended prejudice, yet Minette left the island during the 1791 uprising and never returned. Sorry, Mimi, you miss the pantheon by a breath.

Then came what I like to call, half-ironically, the “warriors”: Andrée Lescot, Andrée Gauthier Canez, and Émerante de Pradines—three women who carried the torch during and after the two world wars. Gifted, brave, but largely forgotten. Andrée Lescot, daughter of a president, studied at major conservatories and embraced Haitian and Louisiana folklore, yet her impact never took root. Privilege does not guarantee legacy. The other Andrée, wife of Valério Canez, the entrepreneur, worked with acclaimed European composers but remained confined to elite salons. As for Émerante, scholar, teacher, and passionate revivalist of Vodou songs, she lacked that final spark. The technique was flawless, the emotion somehow contained. Everything was there except the magic.

Contemporaries

Yole Dérose and Toto Bissainthe, two names that gave me migraines before I had to let them go. They are pillars of Haitian music, with immense talent, technical mastery, charisma, and class in abundance. “Si m pa pase m p ap ka rele viv Nwèl…” rings in my head every December, and Dèy still tears my gut apart. Yet neither ever reached that point where a voice becomes legend. Perhaps Toto spread herself too thin between film, stage, and exile, or perhaps Yole was robbed of her defining moment by grief and illness. Two queens, absolutely, but not quite divas.

Next come TiCorn and Farah Juste, two opposites on the same line. TiCorn, a German by birth but Haitian by heart, froze herself in a postcard vision of Haiti: smiling, colorful, immobile. Farah, the tireless activist, locked her art in the furnace of political anger. Yet a diva must breathe the full range of human feeling, not just one cause or image. TiCorn’s sincerity and cultural devotion could have earned her that crown if her art had carried a more personal imprint. Farah’s courage and voice commanded respect, but her message grew trapped in repetition.

Then Yanick Étienne and Gina Dupervil, two dazzling voices, two sparks that faded too soon. Lanmou nou pran dife remains a classic; Émotionnelle still hits, but emotion alone doesn’t build eternity.

Manzè (Mimerose Beaubrun) and Lunise Morse are forces of nature, pillars of roots music. But their grandeur remains confined to the sacred and the militant. The same applies to James Germain, a magnificent singer with an androgynous voice that earns him the same feminine aura as Michael Jackson or Elton John—both divas certified (and definitely no joke this time).

Mélissa Laveaux and Blondedy Ferdinand represent two opposite extremes. The first is immense talent, perfect control, rare authenticity, yet perhaps too introverted to claim her crown. The second is omnipresent, loud, and ambitious, but lacking the artistic depth to match the aura. Still, both embody two faces of contemporary Haiti: introspection and spectacle.

As for Marie Bedjine and Anie Alerte, the verdict is still open. They’re young, determined, and talented, with room to grow. Anie already owns her identity and voice, pursuing elevated causes with conviction. Bedjine has presence but still seeks meaning and aura. What both need may be the hardest to define: grace? Because real divas don’t force their way through; they glide. They radiate. Their presence is self-evident.

Now that the field is cleared, let’s talk about those who truly carry the soul of a nation.

The Divas

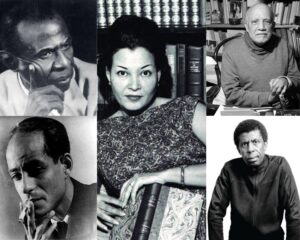

Lumane Casimir (1914–1955)

Born in Plaisance, or perhaps in Gonaïves; her origins remain uncertain, except that she came from the countryside and arrived in Port-au-Prince around age fourteen with nothing but her guitar and talent. The first known female Haitian guitarist, she began humbly, performing near the Champ de Mars. Her career was as short as it was luminous, but I crown her for the same reason I would have crowned Minette: her journey itself was an act of defiance. Nothing in her background predestined her to perform at Haiti’s 1950 Bicentennial Exposition, to travel the world, or to share the stage with Celia Cruz and Daniel Santos. Her voice still echoes through time (Isit an Ayiti, Panama m tonbe, Papa Gede bèl gason). Yet her legacy is tragically under-acknowledged. To rise that far, from such conditions, in a country where class and color were walls, Lumane had to be nothing short of extraordinary. She died young, alone, tubercular, and broken, but divine. Those who met her say she was irreverent, magnetic, and unpredictable. Isn’t that the very DNA of great artists, geniuses, and divas?

Martha Jean-Claude (1919–2001)

There’s unanimity here. Martha was royalty, and doubly a diva: first in Haiti, then in Cuba, where she lived most of her life. A close friend of Celia Cruz, she sang in Creole, French, Spanish, and English, performing in countless concerts. When President Paul Magloire jailed her for a politically charged play, she was pregnant. That tragedy marked the birth of her international career. From then on, she fought tirelessly for civil rights wherever she went. Her voice was deep, tender, sensuous, and also powerful; her smile disarming; her gaze piercing. Every album of “Tata” Jean-Claude is a classic. She’s one of the few who could title a record Je suis la chanson haïtienne (“I Am the Haitian Song”) and no one, even decades later, could argue otherwise. Mic dropped.

Carole Demesmin

Singer, Vodou priestess, woman of resilience. Her first album, Maroule (1980), is a masterpiece that never ages. Her homage to Lumane Casimir on the eponymous track sealed her own immortality. Demesmin may not possess the vocal enchantment of the others I’ve named, but technically she’s unmatched, likely honed during her years of study at Berklee. That precision saved her career after thyroid surgery, allowing her to sing again. She’s perhaps not the most radiant of our divas, but she’s one of the most complete.

Claudette Pierre-Louis

Now in her seventies, she is another life cut short by Haiti’s endless political storms. After the tragic death of Ti-Pierre, her musical partner and husband, a blind keyboard virtuoso, Claudette left for Canada. Together, Claudette et Ti-Pierre released more than ten albums between 1978 and 1990. Their songs were the pulse of a generation. Why Claudette? Listen to Camionnette or Zanmi Kanmarad. That voice floating over Ti-Pierre’s synth is, simply put, the soundtrack of my Port-au-Prince childhood. The soundtrack of millions of us childhood.

Émeline Michel

Born in the mid-60s, she redefined what it means to be a Haitian superstar. Alongside artists like Ti Manno earlier and Wyclef Jean later, she helped introduce the concept of musical stardom to the island. Her music has spanned generations and social classes; it doesn’t age, it matures. She has reinvented herself so many times that one feels she could drop another masterpiece tomorrow and still surprise us all. Go watch La Chanson de Jocelyne and you’ll see the spark already alive in that young woman’s eyes, that lightning in her voice. A.K.I.K.O. remains one of the top five Haitian songs ever produced, and easily in the Caribbean top twenty of the 1990s. Had Émeline started her career in the social-media era, she’d have signed with major labels, headlined Coachella, and probably won a Grammy or two. Beyond her artistry, her activism and grace make her a symbol of modern Haitian womanhood. Writing this piece, she was the first name that came to mind, which definitely says it all.

Rutshelle Guillaume

The most controversial, the woman of the hour. I believe she is living what Aya Nakamura is living in France: the refusal of a nation to recognize itself in one of its own. When people resist Rutshelle, they’re often resisting themselves, their contradictions, their mirrors. Just as Aya has become the new France of the suburbs, Rutshelle is the new Haiti—bold, contradictory, radiant, and flawed. The talent, charisma, and generational influence are undeniable. I don’t even need to throw out a Rutshelle album as reference here, you probably already have most of her tracks in your playlist. So what’s the matter? Probably the same denial we’ve always had: an inability to admit evolution, to see our reflection without filters. Maybe every era gets the diva it deserves. Maybe Rutshelle embodies today’s Haiti, with all its beauty and its chaos. Maybe, like Émeline once did, she’ll outgrow the criticism. Because in the end, she defines and transcends us. Her journey and rise inspire a whole generation of teenagers and young women in search of identity and self-fulfillment.

And if you still disagree, Rendez-vous au sommet.