If I can’t remember the first time I ate in the street, I remember the taste.

Salt and sun. Oil and fire. The clatter of pans tangled with car horns. And the laughter of a machann fritay who, without knowing it, is reinventing the grammar of popular gastronomy. In Haiti, eating has never been a banal gesture. It is a language, a code, a way of existing inside the chaos. And street food is its most honest syntax.

The Street as Kitchen, the Kitchen as Country

In Haiti, the street is everything: a theater, a school, a parliament, a tribunal, a church.

It is also a table.

Between two traffic jams, people stop there to breathe a little life. There is the sting of pikliz in the air, the griot sizzling in burning oil, the fingers that become utensils, the conversations rising like steam. Eating standing up, leaning on a blue cooler or the hood of a car, becomes a way of accepting our humanity, of being home among strangers who somehow feel like kin.

In a country where the elites have long insisted that elegance lies in distance (moun anwo, nèg anlè, m pa ran w…), the people chose proximity: heat, taste, and the hand that serves you. Haitian street food is a school of sharing. One bite here, a joke there, and suddenly the fatigue, the disorder, the fear dissolve. We remember that we are together, imperfect, dangerous even, sometimes to one another, yet pressed close like bodies in a tap-tap or dancers on a kompa beat.

The Kingdom of Fritay

The word fritay is a promise. It snaps in the mouth like a sweet and salty secret.

Behind it lies an entire world: crispy marinad, perfectly golden bannann peze, fried chicken both crunchy and tender, acras that tickle the palate all the way down, and each vendor’s mysterious house sauce, a recipe nobody knows but everyone recognizes by scent. And then there is pikliz, that fiery, vinegary elixir that resets every balance.

Every fritay stand is a tiny sensory democracy.

People gather with the same fervor as in a Vodou ceremony or a football match. There is noise, judgment, laughter, heat. The woman behind the cauldron becomes a Michelin starred chef without diploma or toque. She knows your hunger before you open your mouth. She sometimes serves you more “paske l renmen fòm tèt ou.” She may even hold onto a child’s plate until the parents come back, simply because she wanted news straight from the source or had a score to settle.

Nothing arbitrary. Only love.

Only the laws of this democracy.

A Comestible Memory

Behind every street dish lies a collective memory.

Labouyi in the morning is a grandmother. Pate kòde is the breath of rushing street vendors. Akasan belongs to back to school mornings of tired, indebted parents. Mayi moulen and bread crumb soup belong to uprooted peasants trying their luck in Port au Prince. Even the iced grenadia juice you drink after a chen janbe tells a story, the story of a people who turn scarcity into invention.

These foods, these smells, these gestures repeated on cracked sidewalks are the living archives of a nation. Where institutions fail, cuisine remembers. Where politics divides, taste reunites. In a country that has lost almost everything, except perhaps its palate, street food has become an act of resistance.

Politics of the Empty Stomach

But this culture is fading.

When the era of pen ak ze, BBQ sausages, and Styrofoam spaghetti bowls arrived in the late 1990s and early 2000s, even as a kid, I knew something had shifted. One economy had swallowed another.

The pleasure of cooking for others has long been replaced by the urgency of surviving. Today, young women, often without the ancestral know how, rush into street food to stay afloat. They are chased from sidewalks for “unsanitary conditions”, while the real poisons sit much higher, on the plates of the powerful. I am convinced that every abundance kept to oneself poisons the soul and breeds cruelty.

The prices of oil, flour, and rice keep rising while the cauldrons go cold one by one. Fritay, once a way to feed a family, becomes a luxury for some and a memory for others. Eating in the street, once a gesture of freedom, becomes an act of survival.

And yet they stay, these women of fire, standing behind their dented pots. They hold the front line of national dignity. They feed drivers, students, laborers, dreamers, all those who refuse to die of hunger or erasure. They are our true entrepreneurs. Each bak fritay deserves a line on the stock exchange. They work with no Instagram page, no import license, no lobby, only oil, faith, and incandescent courage.

Love, Deep Fried

In Haiti, love often smells like frying oil.

It is no coincidence that so many first dates happen around a shared plate. Too spicy pikliz, lukewarm orange juice, a nervous laugh, and suddenly the spell works. In the street, everything feels raw, honest, unfiltered. You cannot fake who you are when you eat standing up.

Love, here, is learned through greasy napkins and complicit glances. You can easily get cooked, but there is also a promise of long and deep mutual nutriture in the air.

It is the philosophy of fè l ak sa w genyen, make do with what you have. It is what every street cook does, every pate kòde seller, every mother who turns nothing into a feast. This creativity of scarcity, this poetry of survival, is what makes Haitian street food a collective work of art.

Epilogue: The Taste of Courage

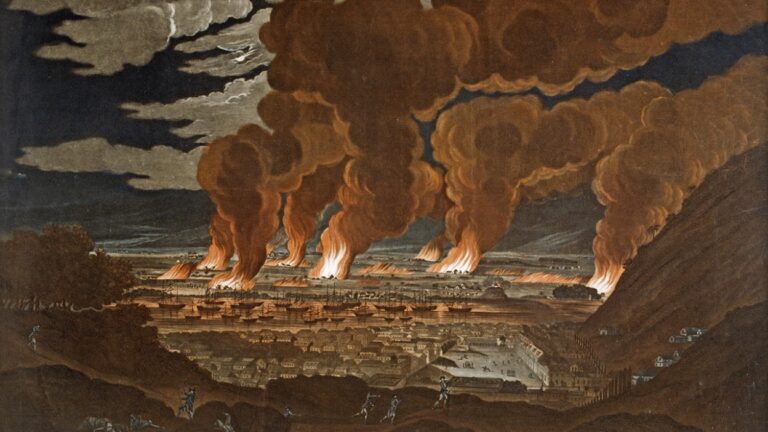

Today, the sound of simmering pots is drowned out by the sound of guns.

Between kale pwa and bwa kale lies a mass grave and the brutal unlearning of our human side. Yet sometimes, turning a corner, a smell returns: oil, pepper, hope. I close my eyes and hear my mother say, “M pa gen anpil, men n ap ka manje.”

“I don’t have much, but we’ll find a way to eat.”

Maybe that is Haiti’s first great challenge, a promise always broken but always repeated, like a chorus.

So to all those women and men who still stand between storms, to those who feed the country without flags or speeches, to those who add spice to our bleakest days, I raise my fork.

Because Haiti, even burned and battered, remains the most beautiful cuisine in the world.