“For I do not understand my own actions. I do not do what I want, but I do the very thing I hate.”

Romans 7:15

It is difficult to begin this reflection anywhere other than from a place of pure subjectivity, but I hope that this perspective, offered sincerely, can grant the necessary legitimacy to what follows. I am fully aware that the very question posed here carries an implicit assertion, one capable of unsettling or offending practitioners, devotees, and admirers of Vodou. Yet the question rises from a desire, and you will pardon the pretension, to restore dignity and to rethink the conditions through which this ancestral heritage might finally grow and evolve.

Many will argue that my position goes against the current. They will point to the renewed fascination of young people, to the cultural adoption of Vodou imagery on social media, to the rising popularity of its symbols and rituals, and they will conclude that the tradition is doing well. They will say that the culture is blooming again. I disagree. Today, Haitian Vodou, both as culture and religion, is faltering. It has become a wounded identity space that wears a mask in order to keep looking like itself. It breathes, but only in the way a body breathes when it refuses to acknowledge it is unwell.

“We all remember a past that never happened.”

Jorge Luis Borges

There is no need to light lamps or invoke the lwa or the saints. I will explain myself, and Legba, who stands at the gate, knows that I am arriving with honest intentions.

To strengthen my right to speak, I should add that I come from a peasant family in the Great South of Haiti. Like many others in the region, my parents were Catholic on Sundays and Vodouisant in times of conflict or illness. Next to the portrait of the Holy Virgin with the infant Jesus, a straw hat covered a machete and a bottle of camphor alcohol wrapped in a red scarf. There were Sunday masses, but also burnt wicks placed inside a small home altar. There were first communion celebrations, and there were dances and offerings to the spirits. My grandmother would fall asleep rolling her rosary, then pour coffee onto the ground for the dead in the early morning, sealing it with a sign. It would have been almost perfect harmony if I had not sensed the embarrassment of my aunts after their moments of trance, if I had not observed their urge to dispose of the feasts and thanksgiving offerings as if they were a burden. As a child I could attend mass and read freely through the bloody epics of the Pentateuch and the terrifying Revelations of John, but I had no access to the room during rituals and offerings.

The picture I have just painted of my childhood, which seems to illustrate perfectly the assumed syncretism of Vodou, must have resonated with many of you. Yet it is false, or rather, not entirely true. In reality, every detail is real, but I arranged and distributed them in a way that would resonate as closely as possible with the collective imagination. I did what horoscope merchants do. They cast a wide net, profile according to the anxieties of the era, and then produce a personalized message for every Aries, Pisces, and Taurus in the world. And the proof that it works is that even the Virgos and Libras reading this may have felt left out for a moment. This is exactly the dead end in which Haitian Vodou has found itself. It answers expectations and fantasies deeply rooted in the collective imagination and moves further and further away from truth.

“So remember Me, and I will remember you.”

Qur’an 2:152

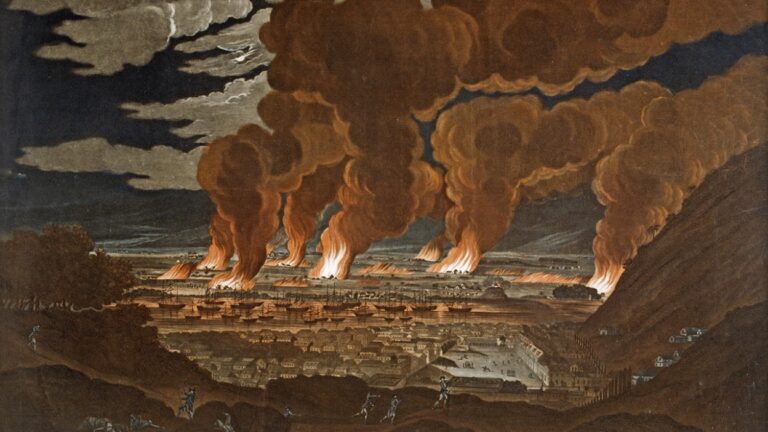

To illustrate my point more clearly, let me slit the throat of a wild pig, meaning, let me return to the night of August 13 to 14, 1791, during the ceremony that preceded the first great uprising of enslaved Africans in Saint Domingue. I am joking, of course, and no animal was harmed in the making of this article. Still, this founding act, the first pact among the enslaved population that would, after a decade of struggle, give birth to the first independent Black nation, has never been celebrated as it should have been.

We waited until 2025 to make it a public holiday. And compared to the magnitude of August 15, the feast of the Assumption of the Virgin, Bois Caïman is almost another joke. Yet this iconic date in the history of this country, this religion, and this culture should have been a foundation upon which to build unity and the national values we claim to seek. Considering its immense importance, August 13 and 14 should have become the greatest celebration in Haitian Vodou, with pilgrimages, dances, prayers, offerings, and gatherings across every corner of the country.

Why has this never been the case? We all know why this religion was marginalized, persecuted, and forced into silence. What we still do not know is what might have changed had it been celebrated with the honor it deserved. What are we waiting for to correct this? Who can correct it? Who must correct it? And how should it be done?

“As people approach Me, so do I receive them. All paths, Arjuna, lead to Me.”

Bhagavad Gita 4:11

Setting aside the fact that the 1860 Concordat was the most intellectually stifling mistake made by the young Haitian nation after the recognition of the independence debt, and setting aside the dominance of the Brothers of Christian Instruction within the national school system, one must ask : what are the so called “indecent” values of Vodou that made us blush so deeply that we collectively rejected our origins and foundations? Because beyond this shocking lack of respect for the very birth of the culture, our relationship with its fundamental values and practices has created and nourished the distortion we continue to carry today, even in this era of the false rehabilitation mentioned earlier.

I am far from an expert, but I will attempt a brief introduction to Haitian Vodou in a few lines. Here is my Vodou 101 for beginners :

- Haitian Vodou is a monotheistic religion. As in Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, believers pray to, serve, and venerate a single God known as Bondye, Granmèt la, or Bondye Papa. And it is not a trinity, by the way. We kept it simple.

- As in Catholicism, where saints guide, help, intercede, defend, and protect, Haitian Vodou, through syncretism, has lwa and saints who watch over believers in an even closer relationship.

- Just as Christianity has secret societies such as the Freemasons, the so called Illuminati, or the Rosicrucians to shape and preserve values and structures, Haitian Vodou has developed societies such as the zobop, the vlengendeng, and the chanpwèl.

- The essential spiritual practice of Vodou consists of entering into connection with the divine through song, dance, prayer, and offerings. These intense moments often result in states of trance among priests and faithful practitioners. These trances, widely criticized and fantasized, are almost identical to Christians speaking in tongues or being filled with the Holy Spirit, as well as the experiences of Whirling Dervishes or the Quakers.

- The spiritual gifts shared within Vodou communities include sorcery, divination or prophecy, healing, and various forms of magic. There is no need to mention that the witch hunts originated in Europe, that the Catholic Church holds countless rituals of sorcery, including candle magic, black masses, kneeling pilgrimages, and the use of totems in petitions to patron saints, and that Jesus himself once cursed a fig tree. Nor is there any need to describe how similar gifts appear in sacred texts such as the Acts of the Apostles and the Epistles of Paul.

In short, nothing in the values or practices of Haitian Vodou seems more scandalous than what is found in other traditions around the world. Zombification, commercialized wrongly by Hollywood, belongs to the same symbolic lineage as the Egyptian practice of mummification. The Gede are as transcendent and dark as the Mexican Día de los Muertos or Halloween. So where does the shame come from?

What has always drawn fascination in Haitian Vodou are its lower passions and its primal instincts. People are far more eager to popularize the hot pepper placed on the Gede’s genitals than the vow of chastity required for spiritual elevation. They highlight the anger and mischief of the lwa rather than the aura of sanctification and love that comes with true consecration. And perhaps, because survival has always overshadowed serenity in this country, the spiritual dynamic that emerges is not flattering. One practitioner goes on pilgrimage hoping to win the lottery, another looks to buy zombies to protect a small shop, another prays to conceive or to shield children from lougarous, another seeks invisibility to evade enemies. A whole spectrum of material and instinct-driven concerns, drifting further and further away from the filial spirit expected of a religious community.

This, inevitably, has made space for charlatans with false gifts of divination, who, like horoscope merchants, know how to exploit hunger, fear, and desire. And you might be surprised to learn that a believer can cross the entire country to pray in the Marie-Jeanne cave before Dambala and Ayida Wedo, seeking fertility in order to become pregnant with another woman’s husband. The troubling part is that these very lwa could just as easily offer the wisdom needed to avoid such a situation.

I am inclined to conclude that the shame was taught to us, imposed upon us, and embedded deeply. And this shame is all the more profound because it is not directed only at the culture but also at the so called contemptible being who carries it. The Black body. The Nigger.

“The greatest trap is to believe what the world tells you about yourself.”

James Baldwin

A shame so deep that the person himself ends up nurturing a clear hatred of his own reflection. Is it not within this same community, the one so often presented as guardian of the roots, that we now find men and women who depigment their skin? Is it not within this same community that mistrust toward others is the strongest? One only needs to visit the lakou outside of patron saint celebrations to discover the lack of reciprocal goodwill within this community. When the fever of showtime for the diaspora and for white tourists seeking intense sensations has faded, what remains are money disputes, betrayals, gossip, and even abuses committed by priests and priestesses who wish to maintain authority and keep followers in submission.

I admit that self hatred extends far beyond Vodou. It is a societal problem. But Haitian Vodou should be the core, the sacred space that allows us to be fully ourselves. It should allow us to accept who we are, all of us. Yes, Vodou is relatively progressive in the way it has always embraced members of the LGBTQ community, but is this an acceptance by default linked to the demands of the spirits, or does it arise from genuine wisdom and spiritual reflection, as it did among the Maya or the Aztecs? These questions reveal that the community has not yet taken the time to think about itself, to define its place within Haitian society, or to educate its followers accordingly.

The question of education is central to any discussion about the future of Haitian Vodou, since it is an oral tradition without sacred texts. When we examine the history of religions around the world and the ways in which they spread, we see clearly how essential writing has been to their growth. We cannot ignore the fact that the population traditionally associated with Vodou has been the greatest victim of illiteracy for more than four centuries, but the numbers have changed significantly in recent years. So what prevents the Mambos, the Ati, the learned dignitaries, and the intellectuals of the tradition from producing manifestos, brochures, guides, or written teachings for practitioners and admirers?

“You give but little when you give of your possessions.

It is when you give of yourself that you truly give.”Kahlil Gibran

Certainly, mass education raises the question of economic structure. But if so, why has Haitian Vodou never defined an economic model for its survival and expansion, as most religions have done? Perhaps if this culture had generated its own resources and developed financial autonomy, respect and recognition would have followed long ago. The traces of slavery appear clearly within this structural void. The enslaved person, having nothing, brought nothing to the altar except a plea for the favor of the spirits. I exaggerate the image without mocking it. Yet the greatest privilege was granted to us long ago. It was FREEDOM.

I understand that this freedom has been contested throughout our history, but is freedom ever fully secured? Do not all nations fight constantly to defend or preserve theirs? What I am trying to say is simple. We do have room to act. Why not a tithe like Christians? Why not regular offerings? Even with a first harvest system based entirely on goods, Vodou could have supported the rise of the peasant class in the economy over time. And if spiritual leaders struggle with money management, why not work with the public sector?

“For where your treasure is, there your heart will be also.” Matthew 6:21. Perhaps even a modest investment in the future of Vodouisants would have encouraged Haitian governments to treat the ancestral heritage with more seriousness. And what about the private sector, which finds Vodou fashionable and fascinating? Why not direct investment in the lakou as centers of community development? This could have given birth to the first Vodou schools, natural medicine clinics, and training centers for priests and priestesses.

It is much easier to dance to Ram, or rabòday, or rara rhythms at two in the morning in the gardens of the Oloffson than to think seriously about the development of the religion and culture that founded a nation. Let us be honest.

“You will know the truth, and the truth will set you free.”

John 8:32

Look. I am surely taking shortcuts and overlooking many parameters, but no one can claim this is a simplistic analysis. The reality is clear. Haitian Vodou is not thought through, not managed, and not administered, to borrow the words of the late Monferrier Dorval. Young people who suddenly declare their belonging by adopting new styles, by reclaiming songs, by mimicking the defiant attitudes of the Erzulie goddesses, Freda and Dantò, aligned with rising feminism, believe they are inventing something. But this is simply the history of the country repeating itself. Nothing is new. Everyone has reclaimed Haitian Vodou to justify a supposed return to the roots. Even Duvalier used it to solidify his power.

We are practicing a constant cultural self appropriation while living inside cycles of collective amnesia. And yes, I may have overestimated my intellectual abilities in that last sentence. But you understand what I mean. For the love of this extraordinary heritage, let us stop pretending. If Vodou succeeds in fulfilling its mission of edification and transcendence, it has so much more to offer this country.

And yet, despite all this, I still believe the treasure is intact. It is waiting for us to remove the mask. It is waiting for us to stop the caricature. If we love Vodou, if we can love ourselves, we must seek the truth. It is only in truth that it can breathe again.

Nan Ginen pa tout lwen sa ankò…